Nitrogen sources for alpine vegetation

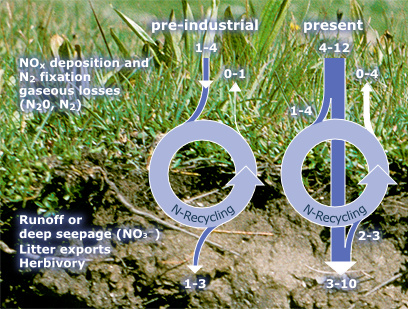

- Direct, natural input of soluble N-compounds with precipitation (nitrite, nitrate, ammonium) as a result of volcanism, lightning, fires, nowadays also by anthropogenic emissions (NOx, NH3 from combustion processes and agriculture). The natural background N-deposition is believed to be smaller than 2 kg N per hectare and year. Current deposition rates in the Swiss Central Alps and part of the North American mountains exceed 4 kg with rates of 10-12 kg ha-1a-1 not uncommon.

- Biological nitrogen fixation by free cyanobacteria (for instance in so-called cryptogam crusts or cyanobacteria in symbiosis with lichens) or by N-fixing bacteria living in symbiosis with roots of plants belonging to certain plant families or genera such as Fabaceae (e.g. Trifolium = clover), some Rosaceae (e.g. Dryas) or Alnus (alder). Biological N-fixation creates a rather small input, commonly insufficient to meet instantaneous ecosystem demand, but over the years these processes contribute substantially to the build-up of the organic N-pool in soils, the ultimate source of biologically recycled N.

- Microbial N-recycling, i.e. the decomposition of dead biomass and breakdown of humus N-pools. This is by far the most important process in late successional communities and well developed soils, but may contribute little to early pioneer vegetation on raw substrate.

9 -

Microbial N-recycling

Because alpine soils are cold, and because the season can be very short, microbial processes run slowly, and alpine soils are considered nutrient poor. By agricultural standards they are. However, as will be shown, this does not reflect the reality for alpine plants, which are adapted to these life conditions.

Note: Most of the extra-anthropogenic N deposits pass through the system or get trapped in recalcitrant forms in soil humus. Yet, by passing through the system these easily available forms of N may change species composition and biodiversity.